Recovering Human Face Geometry

1. Introduction

In this post, we explore how to recover the 3D geometry of a human face using the FLAME model [1]. FLAME is a parametric 3D face model trained on a large dataset of diverse human faces. It represents faces with a compact set of coefficients for identity, expressions, and head pose, making face reconstruction a problem of regressing the right parameters rather than building a mesh from scratch. This approach is both versatile and robust, capable of capturing fine variations efficiently.

We focus on single-image fitting with FLAME, using the open-source flame-head-tracker [3] codebase. This repository provides a modular pipeline for both video-based tracking and single-image fitting. Our discussion centers on fitting the FLAME model to recover a 3D representation from a single unconstrained image.

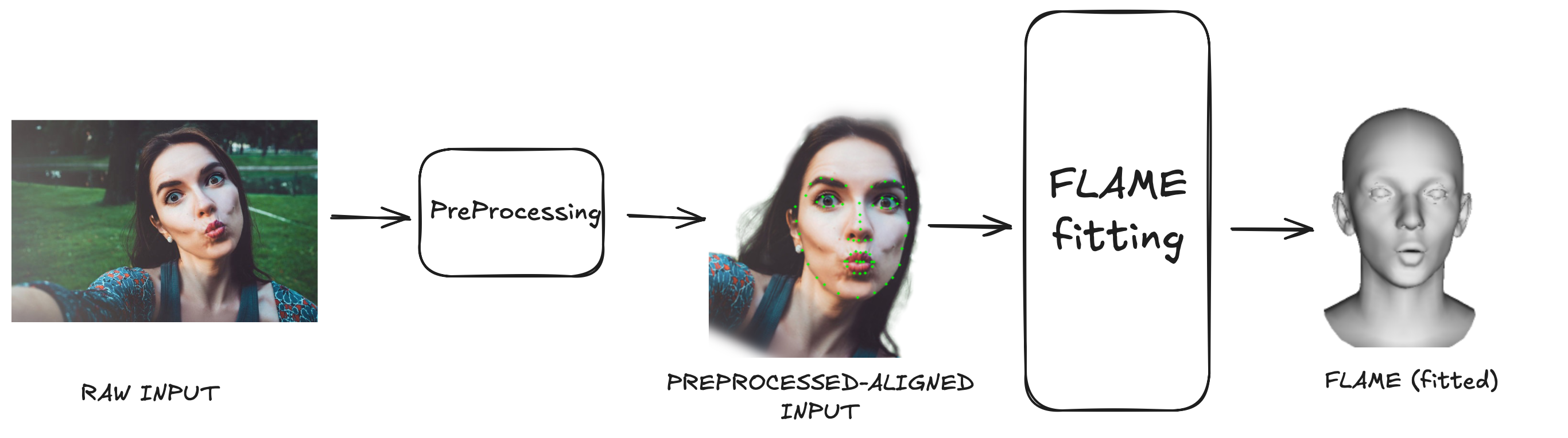

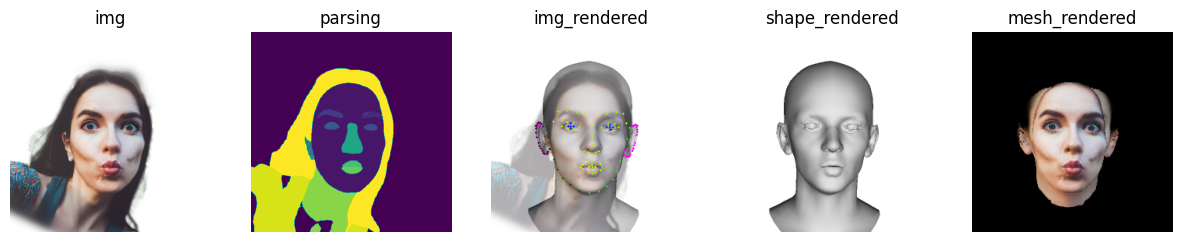

Figure 1: Fitting FLAME to an unconstrained single image.

2. Background: FLAME Model

FLAME is a mesh-based parametric model that represents the human face using approximately 5023 vertices and 9976 faces. Instead of reconstructing a dense mesh from scratch, FLAME encodes each face as a compact set of parameters controlling shape, expression, and pose:

- Shape: identity of the face (bone structure, proportions)

- Expression: dynamic changes (smiling, frowning, etc.)

- Pose: rigid transformation of the head and articulated joints

Figure 2: FLAME variation [2].

This approach enables efficient and realistic modeling of facial geometry. However, FLAME is designed for bare facial structure and does not explicitly model hair, glasses, or other accessories, which can introduce challenges when fitting to real images.

3. Challenges of Single-Image Fitting

Fitting a 3D model like FLAME to a single image is difficult due to limited cues:

- Ill-posed 3D→2D projection: Many different 3D shapes can look identical in 2D.

- Depth ambiguity: A small face close to the camera can project to the same 2D image as a larger face farther away, creating ambiguity in depth.

- Occlusions: Hair, glasses, masks may hide facial features.

- Lighting and viewpoint: Shadows and extreme angles complicate alignment.

These factors mean single-image fitting must rely on strong priors, landmarks, and optimization rather than raw pixels alone.

4. Fitting Pipeline Overview

The flame-head-tracker pipeline for single-image fitting consists of three main steps:

- Preprocessing: Face detection, alignment, parsing, and landmark extraction normalize the input and localize key features.

-

Initialization: Pre-trained models DECA [5] and MICA [6] provide initial estimates of FLAME parameters—DECA for expressions, pose, texture, and lighting; MICA for identity shape coefficients. This initialization step is crucial: a good starting point significantly accelerates convergence and improves the stability of the optimization process.

- Two Stage Optimization: The fitting is refined in two stages:

- Stage 1 aligns the initial FLAME model to the input image by estimating the camera’s 6DoF pose using facial landmarks, applying only global rotation and translation.

- Stage 2 refines all FLAME parameters—shape, expression, jaw and eye pose, texture, and lighting—using either 3D landmark-based optimization or a combination of 3D landmarks and photometric fitting for improved accuracy.

5. Preprocessing

Before fitting the FLAME model, the input image must be carefully prepared to reduce noise and isolate the relevant facial information. The preprocessing step includes:

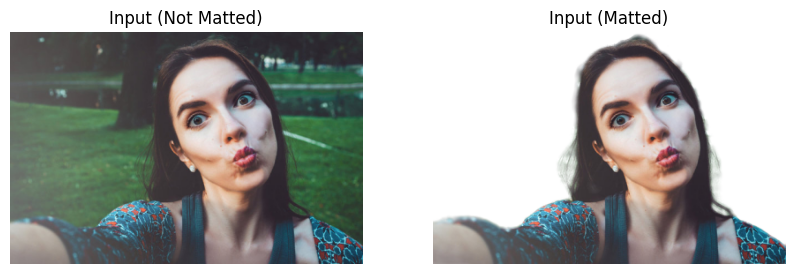

Matting

As a first step, matting is applied to remove the background, isolating the human subject for more accurate and focused subsequent processing.

Figure 3: Matting applied to the input image.

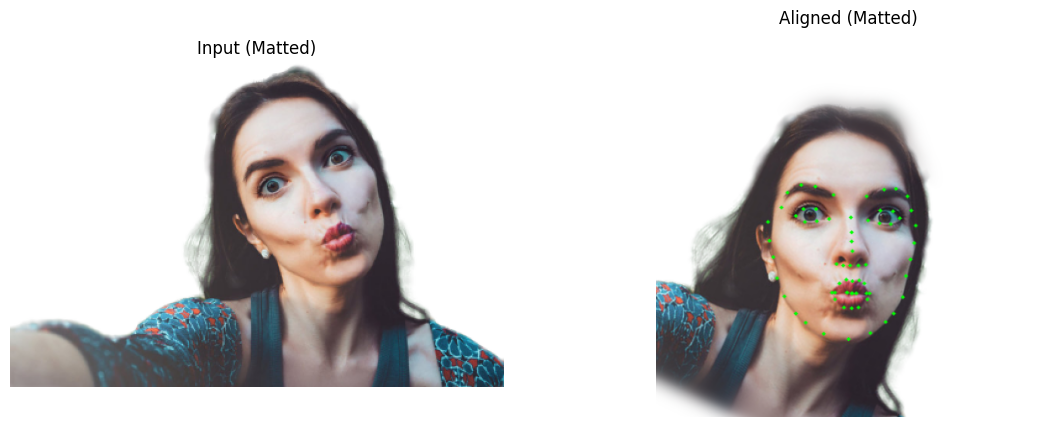

Face detection and alignment

The face is detected and cropped, then aligned to a canonical orientation. This normalization helps the model deal with variations in scale and rotation.

Figure 4: Example of face alignment before FLAME fitting.

Landmark extraction (MediaPipe)

Using MediaPipe, dense 2D facial landmarks are extracted. These serve as geometric anchors for initializing and optimizing the 3D model.

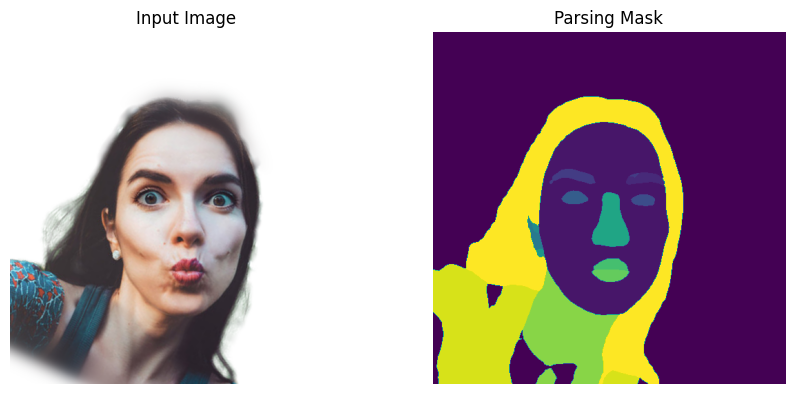

Face segmentation / masking

A segmentation step separates facial regions from non-facial elements such as hair, background, or clothing. By ignoring these irrelevant pixels, the fitting process becomes more robust against occlusions.

Figure 5: Example of face parsing mask used in preprocessing.

Together, these steps ensure that the pipeline starts with a clean, well-aligned face region where key features are accurately localized. This significantly improves the reliability of the subsequent initialization and optimization stages.

6. Two-Stage Optimization

Once the FLAME parameters are initialized, the fitting process is refined through a two-stage optimization strategy. This approach first secures the global alignment between the 3D model and the image, then fine-tunes local details for realism.

Stage 1: Rigid Camera Pose Fitting

The first stage focuses on aligning the FLAME model with the input image using detected landmarks. Here, the system estimates the 6 degrees of freedom (6DoF) camera pose — yaw, pitch, roll, and 3D translation (x, y, z).

- Rigid means that the face model is not deformed during this step: only global rotation and translation are applied to best match the landmark positions.

- This ensures the model is properly oriented before expression, shape, and appearance refinements begin.

Stage 2: Fine Parameter Refinement

With the camera fixed, the second stage optimizes the full set of FLAME parameters, including:

- Shape (identity coefficients)

- Expression

- Jaw and eye pose

- Texture

- Lighting

This stage balances accuracy and stability by applying learning rates and regularization tuned for each parameter group.

| Parameter | Variable Name | Learning Rate | Regularization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression | d_exp | 0.01 → 0.005 | L2: 0.025 |

| Jaw Pose | d_jaw | 0.025 → 0.01 | – |

| Eye Pose | eye_pose | 0.03 → 0.01 | – |

| Shape (photometric) | d_shape | 0.001 | L2: 0.1 |

| Texture (photometric) | d_tex, d_texture | 0.005 | – |

| Lighting (photometric) | d_light | 0.005 | – |

Through this staged refinement, the system moves from a coarse but stable alignment to a detailed and realistic reconstruction, while preventing overfitting to noise or occlusions in the input image.

7. Fitting Modes

The fitting process can be performed in two modes:

- Landmark-based fitting: Uses 2D facial landmarks for alignment and optimization. Fast, robust to occlusions, suitable for real-time applications. Limited detail.

- Photometric fitting: Incorporates pixel-wise losses for higher-quality reconstructions. Slower, more sensitive to occlusions and lighting.

8. Results and Limitations

The outcome of single-image fitting is a set of FLAME parameters that reconstruct the 3D mesh of the input face, capturing identity, expression, pose, texture, and lighting.

Figure 6: Example of single-image FLAME fitting. Input image (left) → fitted FLAME mesh (right).

Limitations:

- Hair occlusion: Not modeled by FLAME.

- Accessories: Glasses, hats, masks can distort fitting.

- Lighting: Strong shadows or highlights may bias optimization.

9. Conclusion & Next Steps

We walked through fitting the FLAME model to a single image using the flame-head-tracker pipeline, covering preprocessing, initialization, optimization, and fitting modes. Applications include avatars, telepresence, facial animation, healthcare, and biometrics.

By combining parametric priors with modern optimization and learning techniques, FLAME remains a strong foundation for 3D face reconstruction research and applications.

References

[1] Li, Tianye, Timo Bolkart, Michael J. Black, Hao Li, and Javier Romero. “Learning a model of facial shape and expression from 4D scans.” ACM Trans. Graph. 2017.

[2] https://github.com/TimoBolkart/FLAME-Universe

[3] https://github.com/PeizhiYan/flame-head-tracker

[4] https://github.com/huseyintemiz/flame-head-tracker (my fork with educational materials)

[5] DECA: Feng, Yao, Haiwen Feng, Michael J. Black, and Timo Bolkart. “Learning an Animatable Detailed 3D Face Model from In-The-Wild Images.” ACM Transactions on Graphics (Proc. SIGGRAPH), vol. 40, no. 8, 2021.

[6] MICA: Zielonka, Wojciech, Timo Bolkart, and Justus Thies. “Towards Metrical Reconstruction of Human Faces.” European Conference on Computer Vision, 2022.